A software engineer's guide to A/B testing

Jul 13, 2023

On this page

- How A/B testing works

- What makes a good A/B test?

- 1. A clear, measurable goal

- 2. A clear hypothesis about why your changes will achieve your goal

- 3. Testing as small of a change as reasonably possible

- 4. A sufficiently large sample size of users

- 5. A long enough test duration

- How to implement a good A/B test

- Monitoring your A/B test

- Analyzing your results

- What if my results are not statistically significant?

- Frequently asked questions

- When should you avoid running an A/B test?

- Can I run multiple A/B tests at the same time?

- Are A/B tests only for product changes?

- Can I stop an A/B test as soon as the results are significant?

- A/B test launch checklist

- Further reading

As a software engineer, you have two options:

- YOLO every change and hope they have the desired impact.

- Track user metrics and run A/B tests to verify your changes have the desired effect.

One is easier than the other, but the easy way rarely works in the long term. This guide is for software engineers who are just getting started with A/B testing. In it, you'll learn:

- How to devise good A/B tests

- How to implement and monitor your tests

- How to analyze your results (statistically significant, or not)

We'll also cover some frequently asked questions, such as when you shouldn't run A/B tests, and we've added a simple A/B test launch checklist to use when you run your own tests.

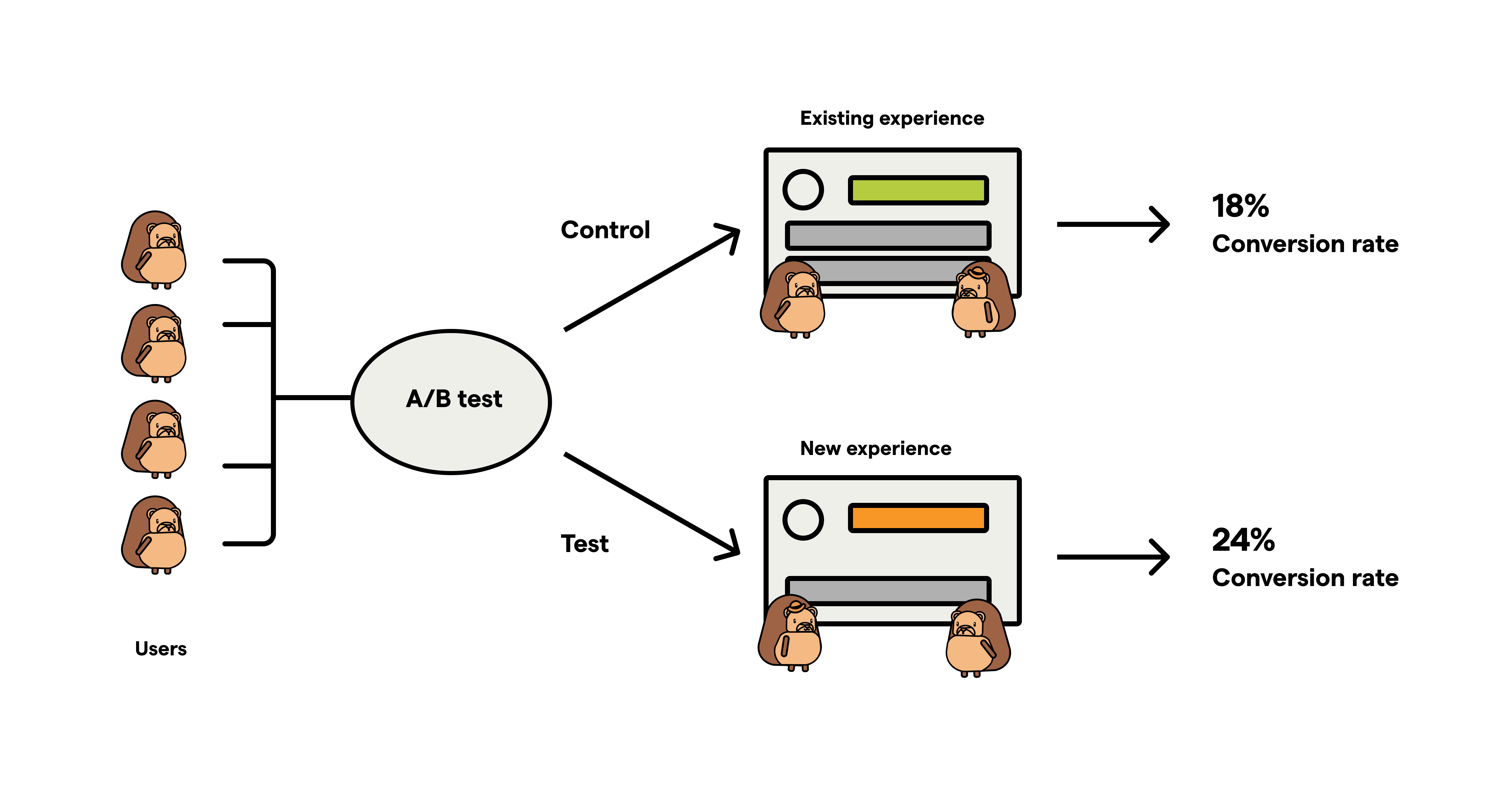

How A/B testing works

Here's a quick breakdown for newcomers – please skip if you're already familiar with the basics.

In A/B testing, you first decide on a goal metric and what change you'd like to see. For example, you may to increase conversion rate or decrease customer churn rate.

With your goal in mind and your code changes ready, you randomly split your users into two (or more) groups:

The control group – These users will experience your product as is – without any of your new changes.

The test group – These users will experience your product with your new changes.

You then run your A/B test to gather data (usually over a few days or weeks) and compare the differences in the goal metric between the different groups.

There are a few different types of A/B test, such as multivariate (where you're testing more than one variation) and multi-page "funnel" tests (where you're testing different user paths), but this guide is focused traditional A/B tests.

What makes a good A/B test?

There are five parts to a good A/B test:

1. A clear, measurable goal

Like "increase paid conversion rate", or "decrease churn rate". This should be a single metric that you're aiming to improve.

"Increase user engagement" is an example of a bad goal, since it's unclear which metric will define success – is it daily active visitors, total number of page views, or time spent in the app? Your test results may show improvements in some metrics, but declines in others.

No clear, measurable goal = ambiguous results you can't action.

2. A clear hypothesis about why your changes will achieve your goal

Not creating a well-defined hypothesis is one of the most common A/B testing mistakes.

A good hypothesis focuses your testing and guides your decision-making by providing a framework for evaluating your results. It should include your goal metric, how you think your change will improve it, and any other important context. For example:

Showing a short tutorial video during onboarding will help users understand how to use our product. As a result, we expect to see more successful interactions with the app, fewer customer support queries, and reduced churn (our primary goal) among tested users.

This is a good hypothesis because it enables you to break down which metrics you'll focus on in your test:

- How many users watch the video

- What portion of the video did they view

- Successful interactions with the app features

- The number of customer support queries

- Churn rate

Then, once you've collected data with your test, you can use these metrics to analyze if your test was a success or not.

3. Testing as small of a change as reasonably possible

Ideally, an A/B test should change one thing at a time. This ensures that any change in user behavior can be attributed to what was changed. If there are multiple changes, it's difficult to determine which one caused the change in behavior.

The caveat here is that too small of change can slow your team down. Since running A/B tests take time, if you're constantly testing small changes, it will take longer to ship large, meaningful changes.

A good rule of thumb to know if your change is too small is if it's unlikely to impact user behavior significantly. You can use qualitative data from user research, quantitative data from existing logging, or previous A/B tests to inform this decision

4. A sufficiently large sample size of users

A large sample size for your test ensures the statistical significance of your results – i.e. if you can be confident your results are due to changes you made, rather than random chance.

To know whether your sample size is large enough, you'll need to know:

The current count or conversion rate for your metric. This is the count or percentage of users who performed the desired action (e.g., click a button, make a purchase, sign up) out of the total number of eligible users.

Your "minimum detectable effect". The smallest change in the count or conversion rate that you want to detect. The smaller the change, the larger the sample size you'll need.

Your desired level of confidence. The industry standard is 95%.

You then use a sample size determination formula to determine if your sample size is large enough. There are many calculators online that will do this for you, so you can avoid calculating this yourself – A/B tests in PostHog calculate this for you automatically.

5. A long enough test duration

Once you've calculated your required sample size, you'll be able to calculate how long your test should run. You do this by dividing your sample size by your daily number of eligible users.

For example, if you're making changes to your signup flow and your required sample size is 1,000 new sign-ups, and your daily number of sign-ups is 100, then you'll need to run your test for 1,000 / 100 = 10 days.

Again, there are many calculators online to help you determine your duration, and PostHog also includes this calculator when creating a new test.

A good rule of thumb is that your test duration should be between one week and one month:

One week is a good minimum since users may behave differently on weekends or weekdays.

One month is a good maximum since otherwise you may delay shipping important product changes.

How to implement a good A/B test

Once you're satisfied your test meets the criteria of a good A/B test, it's time to implement it in your code.

This is typically done using feature flags to randomly assign users to the control or test group, and then logging when users are exposed to their variant – i.e. trigger the code path that checks the feature flag. This enables you to compare metrics in aggregate between the users in your variants.

It's absolutely essential to only log the users in your test who would actually be impacted by your changes. Users who aren't affected by your test should be excluded. If you include unaffected users, their unchanged behavior will mix in with your results, thereby watering down the impact and the clarity of your findings.

To do so, ensure that checking your feature flag and logging their exposure is the absolute last condition you check in your code:

Monitoring your A/B test

Once you've started your A/B test, it's a good idea to check in on it 24-48 hours after launch to ensure that everything is running correctly. Here's a list of things to check:

Check your exposure logging. For example, that the volume of users assigned to the control and test variant is what you'd expect it to be.

Check your event logging – i.e. that you're receiving all the events you expect to receive, and in the right ratios.

Monitor crashes or error rates to ensure that your test is not causing any issues.

Once you're sure that everything is running smoothly, try to avoid frequently checking the results until the test is finished. Checking too often can lead to reactive decisions based on incomplete data. It's usually best to wait until the test ends to make any decisions, as you'll have more accurate data at that point.

Analyzing your results

Once your test has run its duration and you've collected enough data, you're ready to look at the results. What you're looking for is a statistically significant change in any of the following metrics:

Your goal metric.

Any secondary metrics. These are usually metrics that are closely related to your goal metric. For example, if your goal metric is to increase paid conversions, a secondary metric may be to increase sign-ups.

Any counter metrics. These are metrics that ensure your user experience isn't deteriorating. For example, if your goal is to increase sign-ups, you should also verify your churn rate is not increasing.

Most A/B testing tools, including PostHog, will calculate statistical significance for you. To do so manually, you'll need to input the number of users in each variant, and the conversion rate for each metric, into an online calculator.

What if my results are not statistically significant?

This doesn't mean your test was a failure! It suggests that the results observed between the variants could be due to random chance, rather than the change you implemented. Here are few next steps you can consider:

Check you gathered enough data: If your sample size was too small, or your testing period was too short, you might need to extend the duration of your test to gather more data.

Consider smaller changes: If you made a large change, it could be that smaller aspects of the change had different impacts – some positive, some negative – leading to an overall insignificant result. Consider breaking down the change into smaller parts and testing these individually.

Consider larger changes: Conversely, if your change was too subtle or minor, it may not have been enough to affect user behavior. In this case, consider making a more impactful change and then testing that.

Review your hypothesis: It could be that your hypothesis was not correct, and the change you made did not impact user behavior in the way you expected. Take this as a learning opportunity to gain deeper insights into your users.

Accept the results: Sometimes, an insignificant result is the correct result. It tells you that the change you made didn't have the impact you thought it would. This is still a valuable insight, and stops you shipping unnecessary changes.

Frequently asked questions

When should you avoid running an A/B test?

There are costs and trade-offs to running A/B tests. Here are a few scenarios in which you may not want to run an A/B test:

When you lack of sufficient traffic or users, or have time constraints: It won't be possible to gather enough data to obtain the statistically significant results required to make good decisions.

When you have high implementation costs: Sometimes it may create a lot of technical debt to support and maintain both control and test variants of your A/B test.

When you have opportunity costs: The time and resources it takes to implement and analyze A/B tests may be better spent working on other projects.

When there are ethical considerations: It can be tempting to run A/B tests on things such as bug fixes or reliability improvements. While A/B tests can indeed verify your changes are working as expected, you should remember that your users are real people that are relying on your product and so you should not run a test for the sake of it. Proceed with caution when testing such changes!

In the above scenarios, it may be better to rely on qualitative feedback or user research for decision-making.

Can I run multiple A/B tests at the same time?

Yes, you can run multiple A/B tests at the same time, but doing so can complicate things and should be approached with caution. It can be tricky since if tests are not completely independent, the changes being tested can affect each other.

To counteract this, you'll need a larger sample size of users. This is what enables apps like Facebook or Uber to run thousands of tests at the same time, since they have millions (or billions!) of users.

Are A/B tests only for product changes?

No, you can also use A/B tests for infrastructure changes, such as:

If you're considering a new caching strategy or database system, you could split your traffic between the old and new systems to see which performs better.

When you're refactoring your codebase, you can use an A/B test to ensure your refactor does not perform worse.

Can I stop an A/B test as soon as the results are significant?

While it can be tempting to stop a test as soon as the results appear significant, doing so can lead to false positives. This is known as the peeking problem – i.e. the more often you check the results, the greater the chance you'll observe a false positive, a result that appears to be significant, but is actually due to random chance.

To counteract this, predetermine your test duration (based on the sample size required) and only make decisions based on the data collected during the entire duration.

A/B test launch checklist

Launching an A/B test requires careful planning to ensure accurate results and meaningful insights. To help you navigate this, we've put together this launch checklist:

Further reading

- 8 annoying A/B testing mistakes every engineer should know

- When and how to run group-targeted A/B tests

- How to do holdout testing